Ask anyone who teaches online and they’re 99.9% certain to say that encouraging engaging and consistent discussion is the biggest challenge of teaching online. That percentage probably goes down in upper-level discipline-focused courses, but for those of us who teach freshman- and sophomore-level core curriculum courses, this percentage is pretty accurate no matter what the class or the students’ level of online learning experience. Why are (quality) online discussions so difficult to initiate and sustain? This is especially perplexing when you consider how much social media has revolutionized our ability to engage in virtual discussions. Such discussions are a ubiquitous, daily component of almost every millennial’s life. Of course, some would question the quality of those discussions, but I tend to favor some, however questionable in quality, discussion over no discussion at all when it comes to preparing students for online learning. If they come to us already in the habit of using Facebook and Twitter to engage with peers on a regular basis, then shouldn’t transitioning this kind of virtual verbal give-and-take to a course-focused setting, whether it’s Blackboard or a private group on Facebook or Google+, be easy? And once engaging in those discussions we can help them develop the quality of their contributions, right?

Right. But we have to get them there first and that’s the biggest challenge. This is not a case of “build it and they will come.” We’ve tried that. Some of us, recognizing the clunkiness and walled garden atmosphere of most LMS discussion forums, moved to trendier forums, meeting students where they were on Facebook and Twitter. This helped some; maybe we overcame the learning curves inherent in LMS discussion boards and we saw a spike in discussion activity initially as students’ curiosity got the best of them, but this either didn’t work (because students didn’t follow the rules regarding appropriate posts or never learned how to use hashtags to signal course-related tweets) or it didn’t last (as the novelty wore off and students realized it was just the same boring kind of class discussion relocated to their social spaces). [As a reminder, I am focusing here specifically on 100% online courses, as I know several teachers have had success with using social media in face-to-face and hybrid classes to spark discussion and participation.] The problem, of course, is multifaceted. Some of it has to do with students’ perceptions about the value of deep, meaningful discussion about academic texts and issues and their lack of experience with such discussion, triggering fears about how others will view them if they say something “dumb.” Part of it is our inability to transcend the artificiality of such discussions; even relocating a teacher-constructed, forced discussion to an organic forum like Twitter cannot disguise/mitigate the true nature of the interchange. And we’ve only added artificial sweetener to an already artificial ingredient by superimposing rubrics onto the discussion, requiring a certain number of posts and comments, and assigning point values to each post and comment, further de-motivating students who fear they’ll be penalized for inept posts/comments and imprisoning students within an inorganic, regimented system of forced, mimicked responses. So, what’s an online teacher to do?

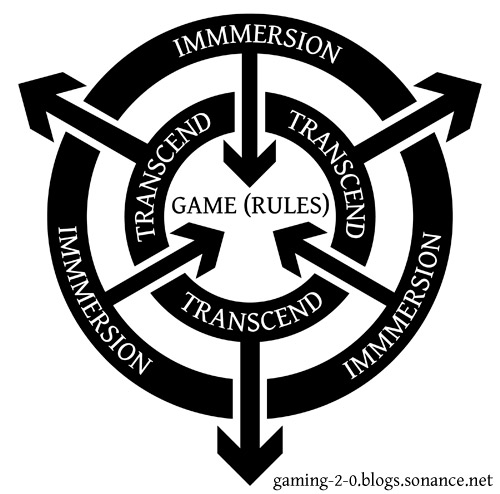

That is the question I was faced with as I began to design my first 100% online first-semester First-Year Composition class for the upcoming Fall term. So, I began to think about what kinds of activities triggered the most engagement and meaningful discussions in the classroom. I ended up isolating two specific kinds of activity: debate and cooperative competition games like the one I designed to gamify required readings. So, my next question became how I could translate those kinds of activities to a virtual space rather than a physical classroom. This question proved to be much more problematic, as both of these activities are based upon physical proximity and the ability to receive and give immediate feedback. And while both involve an artificial construction, the context and rules imposed on the students force them to be creative and to deeply engage with the questions/issues at hand if they want to “win.” So, artificiality is the whole point: these are both games and a game is an artificial construct that embraces its artificiality and uses it to encourage deep player engagement. It just so happened that I was also re-reading Jane McGonigal’s Reality Is Broken at the same time as I was pondering the dilemma of how to redesign these two activities as virtual games. In particular, her chapter on “Stronger Social Connectivity,” which outlined social network games like FarmVille and Lexulous, seemed to hold the answer. While I was not familiar with Lexulous, it immediately reminded me of Words with Friends. As McGonigal points out, these kinds of social network games are typically asynchronous (as are online discussion forums), but are designed to encourage checking in on a regular basis to keep up with and respond to “friends'” activities (something online discussion forums can’t quite seem to accomplish). This seemed to be the blueprint that I needed for the kind of discussion game I was contemplating.

I ended up using Words with Friends as a model and designed three different types of discussion games. The games will be played in a Google+ Community. Each game has a start date/time and an end date/time; during the interval the game is “on” and students can post whenever they wish. In some cases, I imposed a limit to posts in order to discourage students from monopolizing the game and farming points. I decided to make all points earned during the games bonus points; each student’s bonus points will be tallied and recorded on a scoreboard and added to their final course grade at the end of the term (because this is a dual enrollment course, I have to use a traditional grading structure and have not gamified the class beyond the discussion games). The points earned by the highest-achieving student will determine the baseline grade; so, if they end up earning 15,000 bonus points, then all students’ bonus points will be recorded as X/15,000 (again, because this is an online dual enrollment course, I have to use Blackboard’s grade book, which requires a maximum point value for all grades entered). Some games are team-based, so students earn points for themselves and their team and the team with the most points scored earns even more bonus points. I did design rubrics outlining criteria for the kinds of posts expected for each game, but because of the gameful nature of the activities, students can have posts of varying degrees of quality and still earn points and, in the case of team-based discussion games, help their team.

The first game I developed is an online version of my power card reading game. It basically works the same as the in-class version of the game, only without the cards (I’m still working on how to use the cards virtually). Each student will be responsible for posting questions and answers at any time during the period in which the game is “on.” Here’s a breakdown of the guidelines and rules:

- The questions must be open-ended, meaning there is no right/wrong answer, and they must require supporting evidence from the book as part of the answer.

- Each team member may ask no more than three questions.

- Each team member may answer no more than three questions.

- Repeated questions or answers will not earn points, but still count towards a player’s maximum question/answer allowance.

- Players should tag their question posts with their team name so that other players know which team posted the question.

- Players may only answer questions posted by members of the opposing team.

- Players who wish to answer a question must post their answer as a reply to the opposing team’s post.

- A question may be answered by more than one player but be careful of repeating answers.

- Each question and answer will be assigned a point value by me, based on the following scale:

4 = excellent

3 = good

2 = fair

1 = poor

- Points for both questions asked and answered with be tallied and the team with the most cumulative points earns an additional150 bonus points.

The second discussion game that I designed is a version of the in-class debates that I often require students to participate in. Again, this one is team-based and the winning team earns an additional 150 bonus points. I will randomly divide the class into two teams and post the debate topic at the game start time. Here are the guidelines/rules:

- The debate begins as soon as the debate topic is posted.

- I will create two posts based on the two sides of the debate and tag each with the appropriate side.

- You may only argue for the side that you’ve been assigned to.

- Each response must be posted as a reply to the appropriate post and must include both a claim (your reasoning) and grounds (the facts supporting your reasoning). You may have more than one piece of supporting evidence for each claim; in fact, the more grounds you have to support your claim, the better. You can find out more about developing a well-structured and well-supported argument on pages 194-200 of your writer’s handbook.

- Each claim will earn a player 10 points and each piece of supporting evidence will earn them 10 points.

- A player may also respond to a claim by the opposing team with a counterargument, which must also include a counterclaim and grounds. A counterclaim will earn a player 20 points and each piece of evidence used to support the counterclaim will earn them 20 points. Counterarguments should be posted as a reply to the argument being rebutted.

- A player may post no more than three arguments and three counterarguments for full points. After this limit is reached, the points earned will be reduced by half. A player may post no more than six total arguments and six total counterarguments.

- Repeated claims and counterclaims will not earn points but will still count against a player’s maximum number of claims/counterclaims. Grounds, however, may be used to support multiple claims and counterclaims.

Last, I designed a discussion game that requires the students to take turns creating and posting questions about the topic/issue under study that the rest of the class has to answer, using specific kinds of answers. This will the first game that I have students play (with me asking the first question) in order to orient them to the discussion game format and begin helping them develop meaningful discussion posts. The students must restrict their responses to the questions to the following four answer types (which can be combined in any way), with each answer type assigned a different point value:

- Explanation (+10 pts.): this type of post is focused on explaining how something works; what happened and how it happened; what something is or how something is done; etc. (fact-based)

- Argument (+20 pts.): this type of post is focused on presenting an argument with the purpose of persuading others to agree with you (opinion-based)

- Evidence (+30 pts.): this type of post is focused on presenting supporting reasons why an argument is valid, using either primary or secondary sources or your personal experiences/observations (source-based)

- Challenge (+40 pts.): this type of post presents a counterargument or rebuttal to a classmate’s explanation, argument, or evidence (opinion-based)

In this game, I also encourage students to +1 peers’ posts that they think are especially thought-provoking, persuasive, and/or insightful. Each post will earn 1 extra bonus point for each +1 it receives; however, each student is limited to 3 +1’s, so they must be selective with their bonus points (again, to discourage teaming up for point farming).

My hope is that by framing the discussions as games, which acknowledges and embraces their artificiality and encourages both individual and cooperative competition, and making all points earned as part of the games bonus points, which are additive rather than subtractive and encourage experimentation and risk-taking, I can help students overcome their antipathy/animosity towards and fear of online discussion forums and inject a little fun into them in the process. I do not have false hopes that these games will completely alleviate all of the challenges inherent in online discussions, but I hope that it will be one step towards getting students involved and engaged in the process so that those challenges can begin to be addressed.

I know that some teachers have probably been able to effectively address the challenge of online student interactions in other ways. If so, please share your ideas, as I would love to incorporate them into my own design.